"Rain" in Liang Yuanwei's latest series of oil paintings embodies the dynamic momentum of brushstrokes, the very act of painting. We have never truly witnessed rain without motion—rain is a verb. "Rain" is Liang’s revelation of painting as action, unreserved.Liang demands that her canvases bear no signs of revision. This discipline asks absolute commitment to each stroke, while allowing the interplay of gestures, their connections and contrasts, to generate a unique pictorial tension.

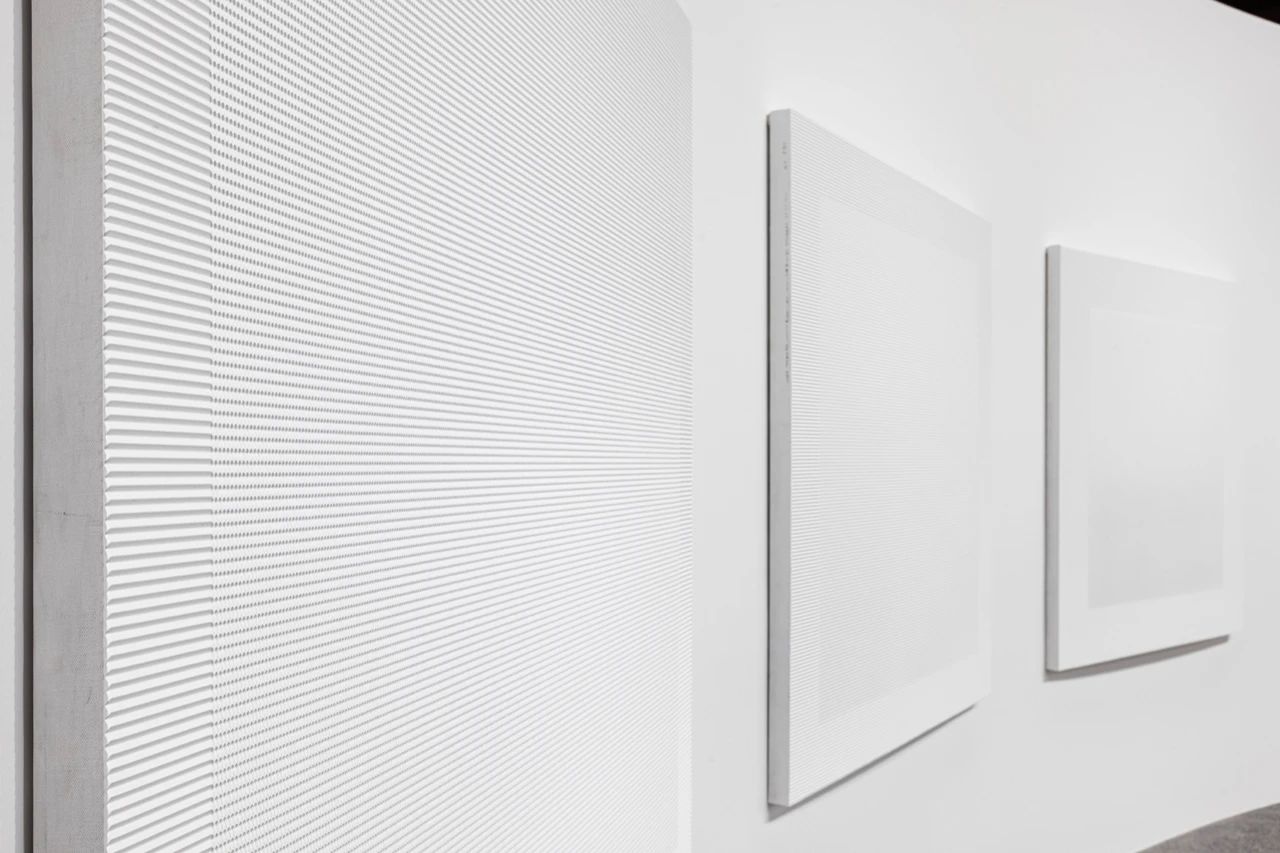

Working with diluted oil paint heightens the challenge of control and compels the movements to be more coherent and compact. While mastery is often born of repeated practice—“practice makes perfect,” Liang consciously pursues a “de-familiarization” of her own technique. For this exhibition, she has set aside fine brushes in favor of coarse implements—scrapers, round cutouts—to spread and texture the paint. New color combinations are introduced between two superimposed layers of diluted paint, generating chromatic shifts that extend beyond her familiar palette. The thinly applied surface is repeatedly worked in varying directions and pressures, gradually exposing the layer beneath. In what Liang calls a form of “extremely limited sculpture,” light is invited to penetrate across the color strata and directional marks, activating a continuous visual fluctuation between the “figure” and the “ground.”Through gestures that feel unfamiliar to her painting practice, the artist comes to sense a certain quality inherent in the movement itself. While the nature of these movements does not change with repetition, their texture grows increasingly vivid through recurrence. In Liang’s latest paintings, each movement is nested within a localized web of surrounding marks, while formally resonating with other gestures across the canvas. These conjure textures from the wider world, evoking a resonant tremor between the painting’s interior and the world beyond it. Within this ongoing, vibrating relationship with the world, the painting’s "content" emerges and recedes.“Pluviophile” is formed from “Pluvio” and “-phile.” Any noun may precede “-phile”; here, “-phile” is a verb. “-phile” signifies Liang Yuanwei’s act of painting from within the world.Such an action draws no meaning from its poles—the beginning and the end, the subject and the object, the “self” and the world; it unfolds through continuous return. It does not move outward toward the world to claim it as its own; rather, it vibrates from within it, alongside it. Through the relentless repetition of this motion, Liang Yuanwei never establishes nor acquires a fixed relationship with the world. Instead, she weaves self and world into a dynamic, interlaced grain.